The primary goal of the orthodox Christian art is the preaching of the word of God and the development of theological speech. In the period of early Christianity, art was symbolic and impersonal. Later, as the theological growth demanded the contribution of a more representational art, the first depictions of the New and Old Testaments appeared, together with the iconography of the Virgin Mary and the saints.

Depictions of Jesus Christ and other sacred figures of Christianity date from the 2nd century onwards. Jesus himself was first depicted in a symbolic way, taking the form of a fish, a shepherd, Hermes or Orpheus, but also through the symbol of the cross.

Christian painting developed through frescoes and portable icons. Mount Athos formed its own distinctive iconographic tradition, so that it became the repository of the orthodox Christian and byzantine art.

Some of the most important iconographic works of Christianity, which are found in Mount Athos, are left unsigned. Thus, we do not know the existence of its outstanding hagiographers except through secondary sources. The artists saw themselves as humble craftsmen, working in the name of the Lord and offering Him their art. Thanks to their work, the monasteries of Mount Athos were enriched with magnificent frescoes and images of unparalleled beauty. From the 16th century onwards, a new trend in byzantine iconography emerged. The representatives of the Cretan school created astonishing artworks in Mount Athos.

Researchers know little about the first icons produced in the monasteries’ churches during the 10th and 11th century. Unfortunately, great buildings of that period were destroyed and some of the most important frescoes were covered by later ones. Over time, all the interior public areas of the monasteries were completely covered by frescoes, while the temples of the churches were decorated with portable icons.

The orthodox byzantine artistic tradition follows an unbroken path through time, from Byzantium to the post-byzantine centuries and modern era.

Mosaics

The earliest surviving works of art in Athos are mosaics. The mosaic decorations of the Athonite Catholicon, as well as the first churches, highlight the special monumental character of the buildings. Soon mosaics were replaced by frescoes, since they constituted a costly and demanding project..

A vivid example of this transition is the Catholicon of the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi, whose walls were originally decorated with mosaics, which were later covered by frescoes. Today only four mosaic depictions have survived.

The first one depicts the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary. The second depicts the icon Deesis, with Jesus Christ seated on a throne, with the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist on either side. Below we see a second version of the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary, dating from the Palaeologan period of the early 14th century. In the southern part of the exonarthex, near the entrance to the chapel of Saint Nicholas, there is a fourth mosaic depicting Saint Nicholas.

As for the floor, it consists of colorful pieces of marble, elaborately arranged to resemble pieces of mosaic.

Frescoes

The Iconographic Program of the Athonite Temples

The temples of Mount Athos constitute a pictorial encyclopedia of byzantine art, as they embody its entire history. Their iconographic program is reflected in the work 'Interpretation of the art of painting' by Dionysios of Fourna. No changes have been made since then.

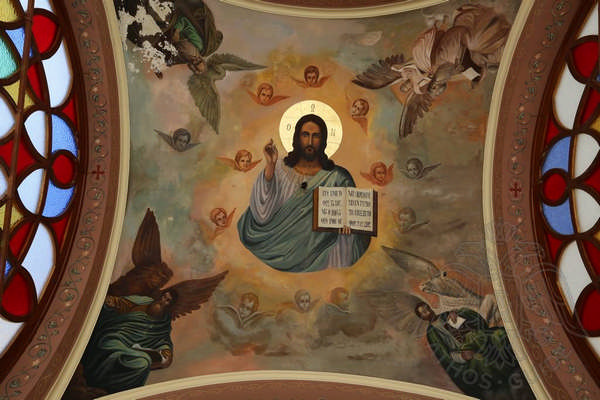

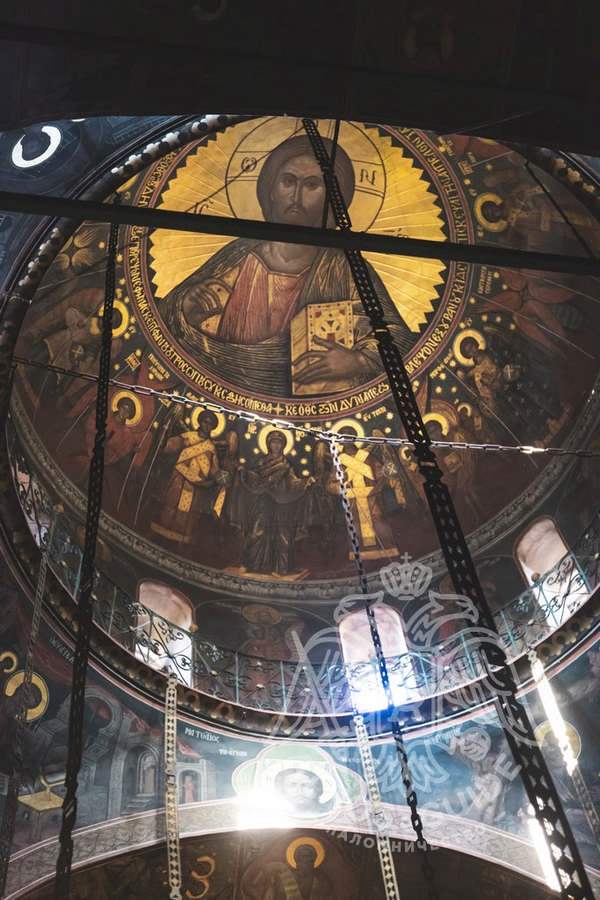

The doctrinal part is mainly reflected in the dome, where the heavenly state of things is symbolized. There is usually the image of the Almighty, who holds the Gospel in his left hand, while with his right hand he blesses the faithful.

Christ is often depicted surrounded by angels. The icon of the Virgin Mary is also depicted on the right and the icon of Saint John the Baptist on the left.

Lower down there are the prophets and the four Evangelists. The doctrinal part is completed by representations of the twelve great feasts. There are the depictions of the Annunciation, the scene of the Ascension and the Pentecost. On the opposite side, on the west wall, there is the Crucifixion, below which there is the representation of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. The Transfiguration is placed in the upper part, between the scenes of the Nativity, the Baptism, the Assumption, the Resurrection of Lazarus and the Entry into Jerusalem. The scene of the Resurrection with Christ's descent to Hades is depicted on the north side of the temple.

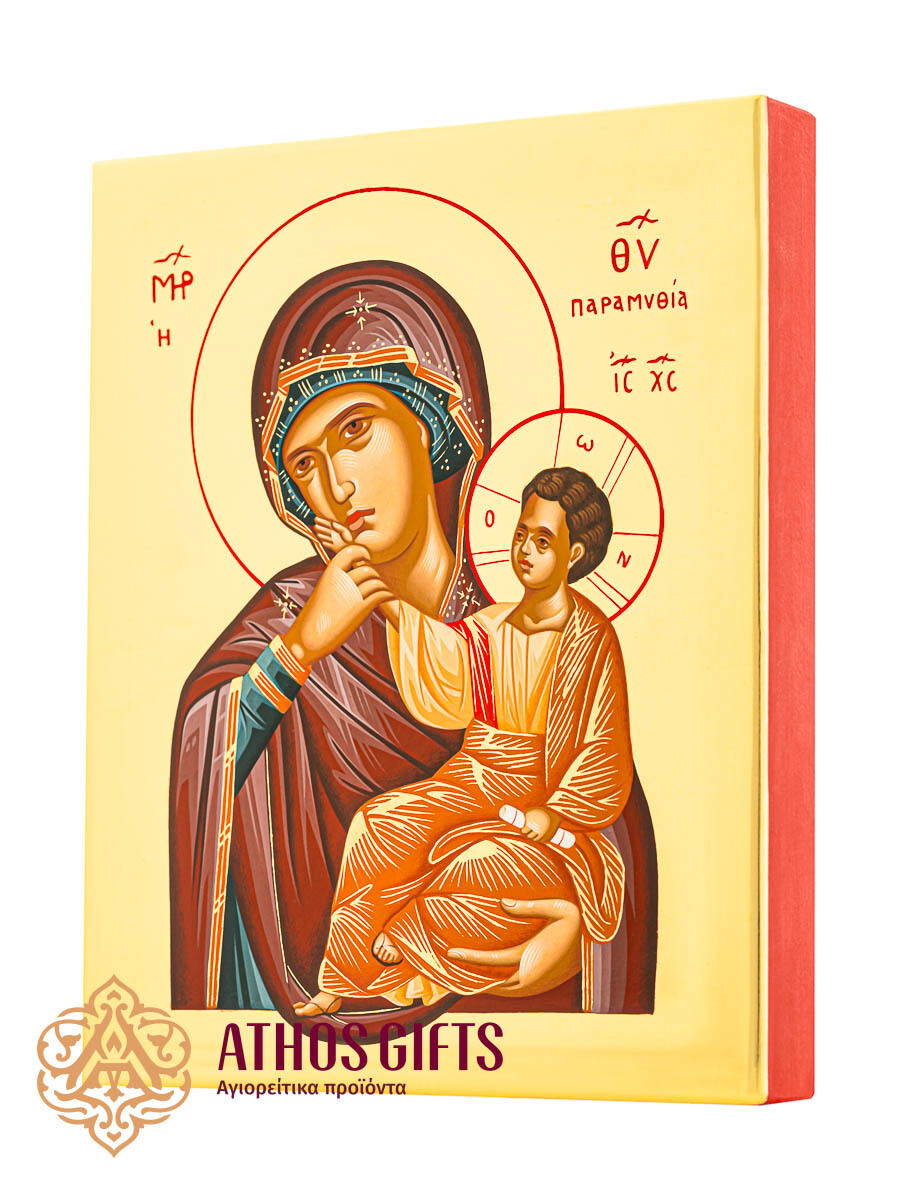

The devotional part of the iconography is placed in the area of the iconostasis and above the sanctuary of the temple. There we see Theotokos blessing the faithful or holding in her arms the Divine Infant. Below the Virgin Mary there are scenes of Jesus Christ and the twelve apostles. The iconographic decoration is completed by the sacrifice of Cain and Abel, the sacrifice of Abraham and others.

The devotional part of the iconography is placed in the area of the iconostasis and above the sanctuary of the temple. There we see Theotokos blessing the faithful or holding in her arms the Divine Infant. Below the Virgin Mary there are scenes of Jesus Christ and the twelve apostles. The iconographic decoration is completed by the sacrifice of Cain and Abel, the sacrifice of Abraham and others.

The historical part of the iconographic program occupies the side walls and is divided into different parts. The upper section contains scenes related to the great feasts of the orthodoxy and the incarnation of Jesus, the middle section contains secondary scenes from the life of Jesus Christ, depictions of miracles and moments from the life of the Virgin Mary. The last zone contains saints, martyrs and hierarchs.

Great pieces of byzantine art are often the depictions of the Second Coming and the Last Judgement above the entrance of the church.

The trapeza of the monasteries is also decorated with great iconographic works. In addition to repetitions of scenes from the Catholicon, representations of the lives of Jesus' disciples, images of saints, ascetics and other important spiritual figures are often added.

Macedonian School

The 13th century was a period of flourishing byzantine art and iconography. However, most works were severely damaged and did not survive. A new creative period began in the 14th century with the artists of the Macedonian school. Great works were created in Mount Athos, in Thessaloniki and in other parts of the Byzantine Empire since then. The name of the school came from the strong prevalence of this style in Macedonia and Northern Greece. The city of Thessaloniki played an important role in the formation of this artistic movement. It was the cultural center, from which the surrounding areas of Athos, Veroia, Kastoria, etc. were influenced.

The most important representative of the school was Manuel Panselinos. He gave to the byzantine iconography a new breath of life, infusing his works with more vitality, light, movement and intensity.

Frescoes of the Protaton

The most important iconographic examples of the art of Mount Athos are found in the Protaton, in the Catholicon of the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi and in the Holy Monastery of Hilandar. Actually, the frescoes of Protaton are associated with the name of the great Manuel Panselinos, for whom we know little. His name is first mentioned in the much later text of Dionysios of Fourna. However, researchers agree that the artist lived and worked during the 1300s. Considering the name Panselinos as a pseudonym, scholars are still searching for his identity. According to the latest research made by historians and monks of Mount Athos, Panselinos is identified with John Astrapas, a famous hagiographer of the Macedonian school of Thessaloniki. At the beginning of the 14th century, the building of the temple of Protaton was destroyed. With its reconstruction, Panselinos was commissioned to paint the new frescoes. With the restoration and conservation that took place in the 1950s of the 20th centuries, the full splendor and magnificence of his work came to light.

The artist used the vast surfaces of the basilica's walls to create his own iconographic program. He divided the surface into four zones using red lines. He filled those zones with images, leaving no gaps. His story begins in the top narrowest zone, where the artist depicted the ancestors of the Lord. The second zone contains scenes from the twelve great despotic feasts. The artwork focuses on the Passion of Jesus Christ, the Descent into Hades and the Transfiguration, which represents Christ in all his divine glory. In the scene of the Ascension, the apostles look up to heaven in wonder, while the Virgin Mary is surrounded by angels. In the third zone, scenes from the life of Theotokos are also depicted. Among them there are the figures of the four Evangelists, Matthew and Mark in the eastern part of the altarpiece and Luke and John in the western part. The fourth zone is the most extensive. The saints of the church are presented in full-face.  The icon of the Mother of Heavens dominates the part of the altar. As the Queen of the world, she is dressed in byzantine imperial robes and looks unusually austere in her majesty.

The icon of the Mother of Heavens dominates the part of the altar. As the Queen of the world, she is dressed in byzantine imperial robes and looks unusually austere in her majesty.

Panselinos’ works are characterized by boldness of line, stunning color combinations, physical movement and drama, while exuding unprecedented spirituality. He was undoubtedly the greatest hagiographer of his time.

Frescoes of Vatopaidi and Hilandar

According to an inscription, the second iconographic project of the Catholicon of the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi was completed in 1312. The earlier iconographic depictions were covered by the new ones, with the exception of a very small area. The blackened surface, as a result of the smoke that had covered the walls over the time, created the need to renew the frescoes, since at that time there was no safe way of cleaning the paintings. The new icons did not alter the contours of the figures. On the contrary only the color was renewed in order to restore the damage.

As for the Holy Monastery of Hilandar, in the 18th century its frescoes were considered the best in the whole of Mount Athos. Unfortunately, in 1803, they were covered by new ones. The earlier outlines were followed here as well, thus preserving the original iconographic program of the church and altering its stylistic character as little as possible.

The frescoes of the Holy Monastery of Hilandar are some of the most remarkable examples of the iconographic art of Mount Athos and the Macedonian school. They are closely related to the frescoes of Protaton, the churches of Thessaloniki and Veroia, while there are also associations with frescoes of churches in Serbia.

Frescoes of the Palaiologan Period

Frescoes of the Palaiologan Period

In the chapel of the Holy Trinity of the Holy Monastery of Hilandar, pieces of unique frescoes of the 13th century are preserved. The figure of Theotokos, of Jesus Christ, an angel, John the Chrysostom and Gregory the Great are represented through an unprecedented richness of colors. In the chapel of the tower of Saint George, the paintings of seven monks, Mary of Egypt and Saint George, dating back to the 13th century, are preserved. Finally, in the Chapel of the Archangels, founded in the 14th century, parts of representations of the same period with Abraham, the apostles, the prophet Elijah and other saints in an upright position are also preserved.

In the Catholicon of the Holy Monastery of Pantokratoros, despite the numerous restorations, parts of the original decoration of the church, which were probably made in 1363, have survived. They consist of a representation of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, a portrait of John the Baptist and individual hagiographies of saints.

The Catholicon of the Holy Monastery of Saint Paul was painted in 1447, but the frescoes were lost along with the building, which was destroyed in 1839. A small part of the art of the Catholicon, depicting Saint Athanasios, is preserved in the monastery's library.

Excellent examples of frescoes of the Palaiologan period can also be found in many other monasteries, as the Palaiologan era was a particularly favorable period for the flourishing of Byzantine art.

Transition to Cretan School

After the fall of Constantinople, the creation of new iconographic works ceased in Athos for about 60 years. The next productive period came in the second decade of the 16th century, giving the art new forms and style. The works that were produced gradually formed the Cretan school.

Constantinople has always been the intellectual and cultural center of the empire, exerting influence on all the other centers of the Greek world. Thus, at the end of the 13th century, the Macedonian school was formed.

The artistic style, however, was soon considered to be too secular, especially by the contemplative fathers, who disagreed with the expressions of the Renaissance movement, elements of which were also elaborated by the Macedonian school. This style, shaped by elements of humanism, no longer satisfied the monks, for whom the divine light took always precedence over human nature. Thus the search for a new way of expression has begun.

A large part of the hagiographers of that time travelled to Crete. It was from this island that a new artistic trend has begun, which took the name of the Cretan school and shaped the post-byzantine art of the last years of the 15th century.

Cretan School

Art remained faithful to byzantine ideals. Its representatives kept the restrained movement, the calmness and spirituality of forms. Their works are characterized by dark colors, testifying to a particular ascetic style.

The individual episodes of the frescoes are separated by wide red stripes, while the influence of the portable icons is quite noticeable.

Although the Cretan school officially appeared in Mount Athos in 1535, with the hagiographer Theophanes, elements of the Cretan style can be observed from much earlier. However, the hagiographer and the exact year of the introduction of the new expressive media remain unknown. These representations include, among others, the hagiography of Saint Athanasios and the great hermit Gregory Palamas. The representation of Jesus Christ, seated on the throne with the twelve apostles standing beside him just before the moment of the Judgement, is the greatest depiction of this genre.

Although the Cretan school officially appeared in Mount Athos in 1535, with the hagiographer Theophanes, elements of the Cretan style can be observed from much earlier. However, the hagiographer and the exact year of the introduction of the new expressive media remain unknown. These representations include, among others, the hagiography of Saint Athanasios and the great hermit Gregory Palamas. The representation of Jesus Christ, seated on the throne with the twelve apostles standing beside him just before the moment of the Judgement, is the greatest depiction of this genre.

On the north side of the cross there is a staircase leading to heaven. An ascetic is climbing there, symbolizing the difficult path of the monastic life. To the right of this scene there is an allegory of death, where angels and demons lead the souls of people.

Great Artists of the 16th Century

The most important representative of the Cretan iconographic tradition of Mount Athos is undoubtedly Theophanes. Born in Crete at the end of the 15th century, he first appeared as an iconographer in the Monastery of Saint Nicholas of Meteora in 1527, where he created some of the finest mural works of all time. At that time, he was already a monk. His first work in Mount Athos is located in the Catholicon of the Holy Monastery of Great Lavra, dating back to 1535, while his last, dated to 1546, is found in the Catholicon of the Stavronikita Monastery. We can therefore conclude that Theophanes remained in Mount Athos for at least 12 years. He ended his life in Heraklion, Crete, in 1559.

Theophanes was, among other things, a great teacher. Wherever he worked, he was surrounded by a large number of disciples who later continued his iconographic work in the monasteries of the Athonite peninsula and elsewhere.

The Catholicon of the Monastery of Great Lavra, which served as an architectural model for all other churches in Athos, also became an example to the interior decoration of the temples both within and beyond the Athonite community.

The Catholicon of the Xenophontos Monastery was decorated by another Cretan artist, Antonios, in 1545. In 1902, the frescoes were covered with repaints. At the entrance of the church, there is an image of Jesus Christ, accompanied by an angel holding a cross, reminiscent of Panselinos' frescoes in the Protaton. The scene of the crucifixion is accompanied by depictions of the sun and the moon covered with a translucent veil, symbolizing the darkness that covered the earth from the sixth to the ninth hour. In the apse of the Holy Altar, behind the iconostasis, the figure of the Holy Virgin Mary is preserved. The narthex was frescoed a bit later, in 1564.

Another prominent Cretan artist in Mount Athos was Tzortzis. He painted the Catholicon of the Dionysiou Monastery, following the style of the great Theophanes, under whom he was taught the art of iconography. However, his work highlights his talent and independence from his teacher's influence, allowing him to infuse a distinct personal style into his byzantine figures.

The chapel of Saint Nicholas at the Holy Monastery of Great Lavra is also decorated by remarkable frescoes. The decoration of the chapel was completed in 1560 and is attributed to the artist Frangos Katelanos. Although he does not seem to have been trained under Theophanes, his work shares many common features with the latter's style.

The chapel of Saint Nicholas at the Holy Monastery of Great Lavra is also decorated by remarkable frescoes. The decoration of the chapel was completed in 1560 and is attributed to the artist Frangos Katelanos. Although he does not seem to have been trained under Theophanes, his work shares many common features with the latter's style.

The Decline of the Cretan School and the Emergence of a new Iconographic Style

The 17th century did not see the rise of notable art in Mount Athos, with only a few cases of iconographic activity that are rather exceptions. Among these there are the decoration of the font in the Great Lavra Monastery (1635), the chapel of the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi (1678) and the trapeza of the Docheiariou Monastery (1700). Extensive iconographic works were carried out only at the Iviron Monastery, funded by the rulers of Iberia. The chapels of Saint Nicholas and the Archangels in the Catholicon of the monastery were decorated in 1674, while the gatekeeper's chapel was decorated in 1685. Among the works of this period, there are depictions of ancient Greek philosophers such as Sophocles, Thucydides, Plato, Aristotle, and Plutarch.

Overall, during this century, a marked decline in iconographic art was observed on the Athonite peninsula. This was initially attributed to the general decline of arts and intellect in the broader Greek area during the Ottoman period, due to the ongoing pressures of the conquerors and the resulting poverty. The second reason for the decrease in artistic activity was the previous completion of the iconographic work in the already existing churches. Finally, the trend towards isolation and monastic solitude did not favor large and extensive works during that time.

However, the decline in major iconographic works coincided with the flourishing of the art of portable icons.