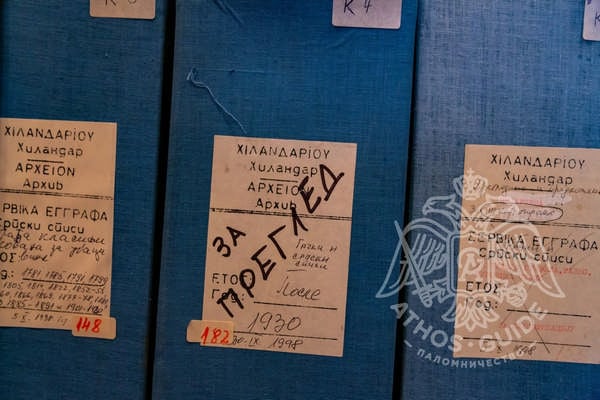

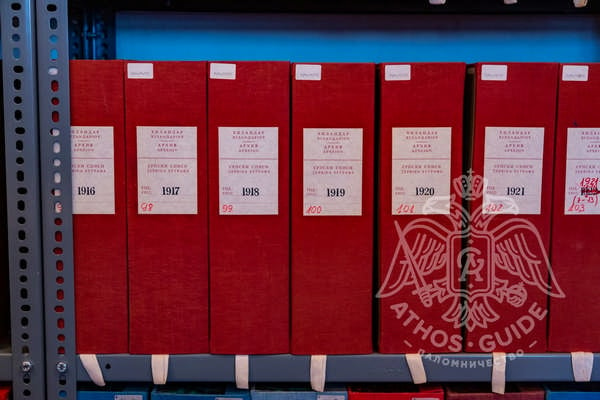

A large number of books and manuscripts from the Byzantine and Ottoman eras are kept in Mount Athos. These archives relate to the organization and history of the monastic community. Relevant documents are also found outside the monasteries, in libraries all over the Greek state and in the archives of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

The archive of the libraries of Mount Athos can be divided into subcategories according to the year of writing, the language, the institution of publication and the content. Chronologically, books and manuscripts can be divided into works from three different periods: the Byzantine, the Ottoman and the modern era. Linguistically, they can be divided into Greek, Latin, Georgian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Romanian, Russian and Turkish texts. As far as their origin is concerned, they are distinguished according to the publisher of the respective edition. Finally, regarding their content, there are works of a legislative, economic or administrative nature, while there are also many texts containing references to famous historical figures.

The manuscripts of Mount Athos can be categorized as follows:

1.The Typikon

The Typikon is a kind of charter, which forms the constitution of the monastic state of Mount Athos. During Byzantine times this document was ratified by the emperor himself, while during the Ottoman period it was ratified by the patriarch, since the sultan was not personally involved in matters concerning the religion of the enslaved populations.

The first Typikon of Mount Athos was published by John Tsimiskis in 971. The second was published by Constantine Monomachοs in 1045. From the beginning of the 19th century this document was renamed "General Regulation", while today it is referred to as "Charter".

The first charters and regulations of Mount Athos were drawn up by the founders of the monasteries, such as Saint Athanasios the Athonite.

2. Administrative Documents

Administrative documents concern economic matters, the regulation of borders and the delimitation of territories. They are usually special decrees or imperial golden bulls.

3. Ecclesiastical Documents

These manuscripts include documents certified by the patriarch, which often have the same power as an imperial decree.

4. Local Government Documents

The manuscripts of the local administration concern the decisions of the Protaton on matters of internal administration, define the relations between the monasteries and regulate the way they operate.

5. Private Documents

Private documents are considered to be the various documents, agreements, leases and sales contracts.

The monks have always been aware of the importance of preserving the manuscripts, as they recognized their great value for the history of Mount Athos. Thus, most of them have survived to this day.

Except for cases of major disasters, such as fires that prevented the preservation of documents, many have reached us today through copies. Indeed, in many cases, the monks have tried to restore the destroyed manuscripts by asking the competent authorities for their republication.

These documents are of particular importance not only for the study of the history of monasticism in Mount Athos, but also for the study of the Byzantine state and society at that time.

These documents are of particular importance not only for the study of the history of monasticism in Mount Athos, but also for the study of the Byzantine state and society at that time.

Researchers became interested in the bibliographical wealth of the athonite state from the 18th century onwards. One of the first to talk about Athos was Barsky, who visited Mount Athos twice, in 1724 and 1744. Ouspensky's presence has also been important. Having secured letters of recommendation from the Tsar and the Patriarch of Constantinople, he visited Athos for the first time in 1845, returning to the peninsula again in 1858. Today his work is kept in the Historical Museum in Moscow.

The first attempt to catalogue the manuscripts of Mount Athos was made in the early 20th century by Ouspensky. His study led in 1873 to the publication of some documents of the Holy Monastery of Saint Panteleimon with the help of Russian and French scholars.

Monastic Libraries

From the very first moment of their foundation, monasteries were engaged in the creation of libraries. As today, there has always been a monk who took on the duties of the librarian, while the libraries were housed in separate rooms.

According to the few surviving catalogues of the monastic libraries, almost all of them contained primary texts of the Bible and works of the Church Fathers, Basil the Great, Saint John Chrysostom, Saint Gregory the Theologian, Saint John Damascene etc. Many of these were read during the meals at the trapeza.

The Athonite libraries were originally formed from donations of the monastery founders.

The works of classical authors, which many scholars consider to be the foundation of Christian education, are rarely found in monastic libraries. However, many monks had their own private collections, which were arranged according to their personal preferences. Thus the libraries were constantly enriched by the donations of monks and ordinary lay people.

Calligraphers of Mount Athos

The Typikon of John Tsimiskis, compiled in 972, was signed by the monk Nicholas, abbot and calligrapher of Mount Athos. Saint Athanasios also mentions in his writings a specific calligrapher, John. There are seven manuscripts written by him dating from 984 to 995.

Ten manuscripts of the first quarter of the 11th century are signed by Theophanes of the Monastery of Iviron. Only one of them is kept in the monastery to this day. It dates from 1007 and contains the teachings of Saint John Chrysostom, while the others are in libraries in Vatican, Moscow, Paris and London.

In the early 16th century the art of calligraphy reappeared in Mount Athos with a greater number of teachers and students.

Among others, there have survived manuscripts by the monk Sophronius from the Holy Monastery of Koutloumousiou, dating from 1542 to 1551. One of them is kept in Moscow.

In the middle of the 16th century, there stands out the figure of Daniel from the Konstamonitou Monastery. At the end of the 16th century, appeared the monk Matthew from the Holy Monastery of Great Lavra. He was a notable author of historical and even revolutionary texts, through which he urged the enslaved Greeks to rise up and overthrow the conquerors.

History of the Libraries

The archive in the monastic libraries is today very meagre compared to earlier periods of prosperity. The libraries of Mount Athos, like the libraries of other Orthodox regions in the East, were plundered more than once. Turkish invaders, foreign rulers, numerous fires and a multitude of pirates repeatedly caused irreparable damage.

In 1535 the library of the Monastery of Esfigmenou was looted. Nine monks were captured and the monastery suffered great destruction. Years later, the monks found it very difficult to locate and redeem the stolen relics, manuscripts and archives of that period.

With the fall of Constantinople and the other intellectual centers of the Byzantine Empire, the interest of European rulers and philosophers focused in Mount Athos. Numerous scholars arrived from all over the world to study and compare manuscripts and archives with the material in the Athonite libraries.

From the end of the 15th century onwards, manuscripts began to circulate in the West, which continued until the mid-19th century.

Catalogues of the archive

The calligraphers of Mount Athos were often skilled painters. They decorated the manuscripts with elaborate drawings and rich iconographic representations.

Illustrated manuscripts were produced in Mount Athos from the 10th to the 19th century. They were undoubtedly a real treasure of the athonite state. Indeed, many of them were stolen and ended up in private collections.

To date, about 500 such manuscripts have survived, while the total number of miniatures is close to 5,000. The difficulties faced by the monasteries over the centuries, as well as the high humidity of the buildings, often caused damage to the archives. Today, private and state institutions have taken care of photographing all the miniatures, thus creating a complete archive on the basis of which the four volumes of the project “Treasures of Mount Athos” have been compiled.

The illustrations are placed in different parts of the manuscripts. Sometimes they occupy the entire page, while others are located at the beginning or the end of the text. Particular attention is paid to the portraits. There are depictions of the four Evangelists, saints, prophets, martyrs and Fathers of the Church.

Furthermore, there are numerous representations from the Old and New Testaments. The stories of Joseph, Moses, Job and David are particularly popular.

Geometric patterns and elaborate plumes accompanied by images of birds, animals or flowers are incorporated into portraits and narrative representations. The text prototype is equally stunningly decorated, enriched with images of people, animals, plant motifs and other decorative elements.

Among the most remarkable manuscripts of the Byzantine period there are the following:

- The portrait of the Evangelist Mark contained in the Gospel of the Holy Monastery of Philotheou.

- The parchment codex 61 of the Holy Monastery of Pantokrator dating from the 9th century. It contains 97 icons of the New and Old Testaments, as well as the lives of the Virgin Mary and the saints.

- The parchment codex 247 of the 9th century in Iviron Monastery, which contains an icon of the four Evangelists standing full-length, holding books in their hands.

According to tradition, the Gospel in the sacristy of the Monastery of Great Lavra is a gift of Nikiforos Fokas. This great codex is richly decorated with silver, gold and precious stones. It contains three images that occupy the entire page. It depicts Resurrection, Nativity and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. The parchment Gospel of the Protaton number 41 also contains magnificent depictions of the Evangelists.

According to tradition, the Gospel in the sacristy of the Monastery of Great Lavra is a gift of Nikiforos Fokas. This great codex is richly decorated with silver, gold and precious stones. It contains three images that occupy the entire page. It depicts Resurrection, Nativity and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. The parchment Gospel of the Protaton number 41 also contains magnificent depictions of the Evangelists.

The 12th century left Athos a great legacy of miniature paintings. However, in the 13th century, the number of miniature treasures began to decline. The problems faced by the Byzantine Empire did not create a fertile ground for the production of works of art. Of course, miniature works continued to be created in Mount Athos, though their number was much smaller compared to the previous two centuries.

Not enough examples of illustrated manuscripts survive from the 15th century. The most typical representations are those of Saint Basil the Great, Saint John Chrysostom, Saint Gregory the Theologian, etc.

A few new manuscripts appeared in the following century, as there were no skilled craftsmen and no suitable materials. This was the difficult period of the first century of the Ottoman rule, during which there was a complete decline in culture and art. Miniature printing reappeared in the middle of the 16th century. During this period, impersonal representations were favored, mainly decorated with floral and geometric plumes.

This increased production lasted all throughout the 17th century, after which there was again a general decline in calligraphy and miniature painting.

Miniatures in different materials

The miniatures of the 13th century are of particular interest in terms of their technique and style. The influence of the West was particularly strong, while there was also an extensive use of many different materials.

The wooden diptych of the Holy Monastery of Hilandar is an important relic, as well as the diptych of the Holy Monastery of Saint Paul. The former consists of two wooden plates measuring 0.30 x 0.24 each, covered with a gilded surface and precious stones. On each plate there are six rectangular and six square sections of small dimensions, within which there are inset letters protected by pieces of glass. The diptych of Saint Paul is equally composed of two wooden plates, measuring 0.30 x 0.21, with a total of 26 miniatures. Each plate consists of a central rectangle containing a miniature. A rectangular space is formed at each corner. In the center and corners of the panels there are representations of the 12 great feasts, the symbols of the Evangelists and the saints.

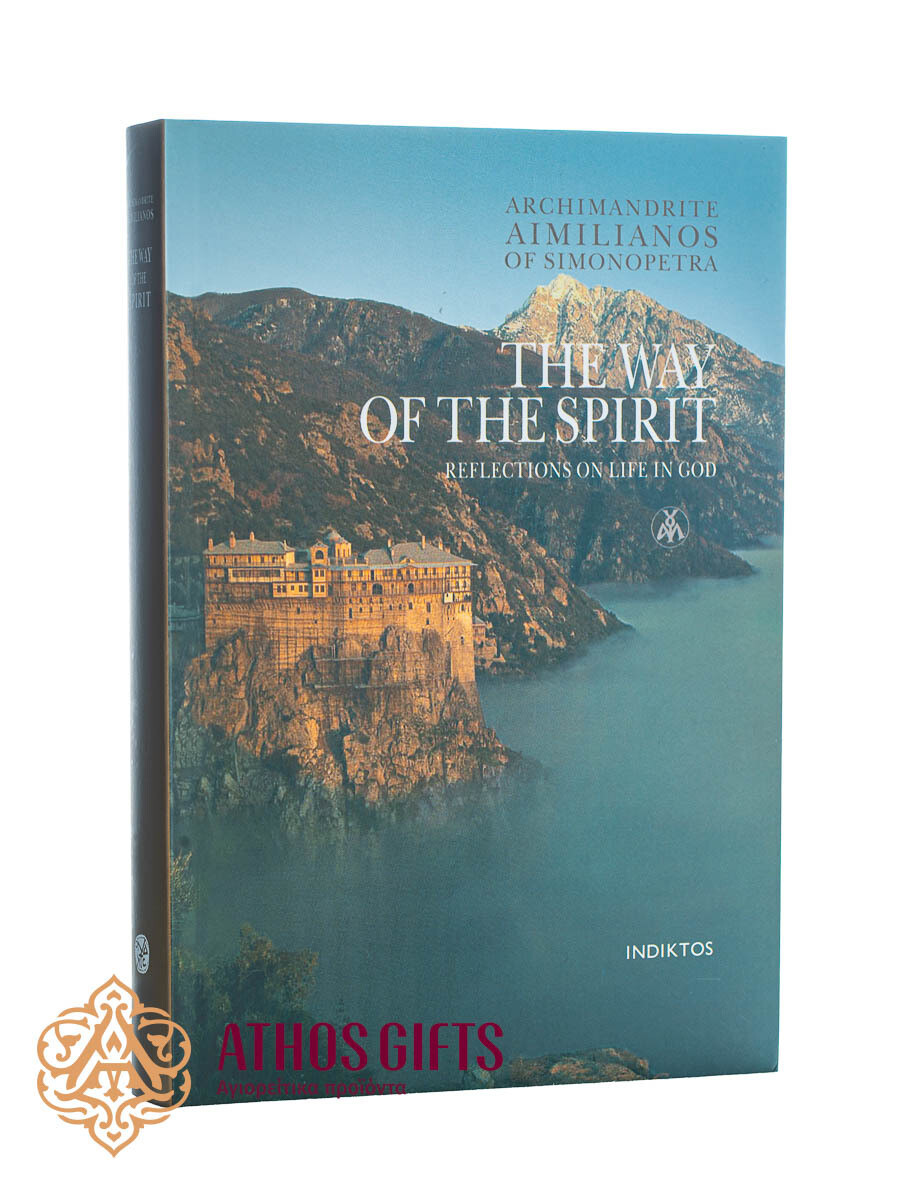

The printing presses of the monasteries

The monasteries and sketes of Mount Athos often have their own printing presses. Particular attention is paid to the way of printing, the quality of the paper and the bounding of the books.

The case of the printing houses and the works that have been printed there, requires extensive research in order to identify earlier unknown editions.

Finally, most monks have their own personal libraries, which are undoubtedly of great historical value.